Module 7#

Agreement Protocols#

- The need for such algorithms is to solve the problem of getting into a consensus

- When a distributed system engage in cooperative efforts, process failure can become a critical factor

- Processors may fail in various ways, and their failure modes are central to the ability of healthy processors to detect and respond to such failures.

The system model/Assumptions#

- There are n processors in the system and at most m of them can be faulty

- The processors can directly communicate with other processors via messages

- A receiver computation always knows the identity of a sending computation

- The communication system is reliable

Communication Requirements#

- This model does not work in an asynchronous model

- Synchronous communication model is assumed in this section:

- Healthy processors receive and reply to messages in a lockstep manner

- This sequence is called a round

- In the synch-comm model, the processes know what messages they expect to receive in a round

Processor Failures#

- Crash fault: Abrupt halt etc

- Omission fault: Processor omits to send required messages to some other processors

- Malicious fault: Processor behaves randomly and arbitrarily, these faults are also known as Byzantine faults.

Message Types#

- Authenticated messages (signed): assure the receiver of correct identification of the sender

- Non authenticated messages (oral): are subject to intermediate manipulation

Agreement Problems#

| Problem | Who Initiates Value | Final Agreement |

|---|---|---|

| Byzantine Agreement | One Processor | Single Value |

| Consensus | All Processors | Single Value |

| Interactive Consistency | All Processors | A vector of values |

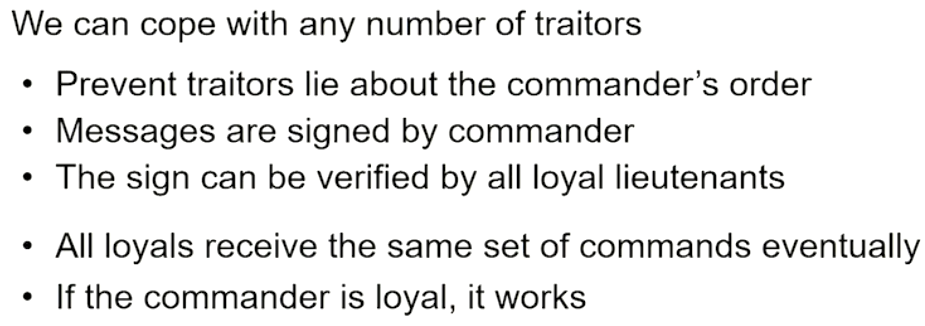

What happened at Byzantine#

Byzantine Agreement#

Impossibility Condition#

- Theorem: There is no algorithm to solve this problem with only oral messages, unless more than two thirds of the generals are loyal

- Impossible if, \(n \le 3f\) for \(n\) processes, \(f\) of which are faulty.

- Oral messages are under control of the sender: Sender can alter messages that it received before forwarding it

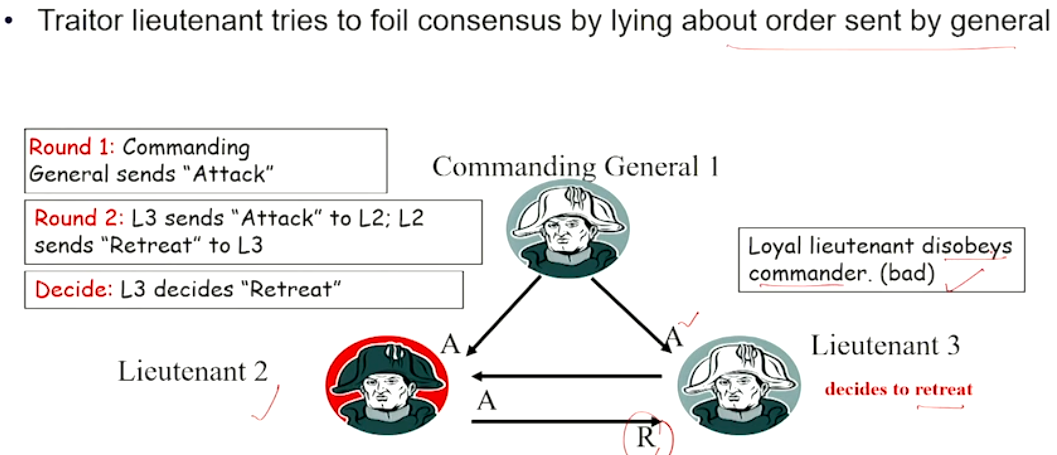

Case 1#

Case 2a#

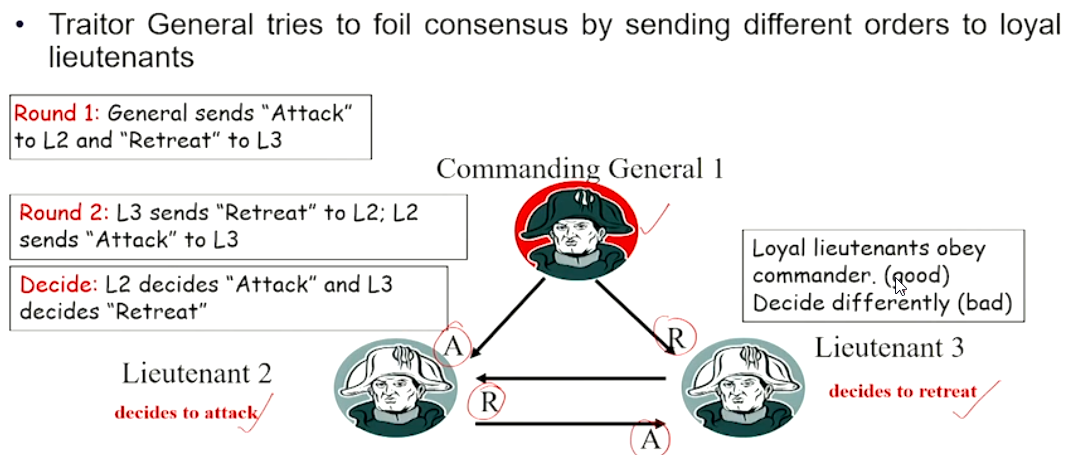

Case 2b#

Case 3#

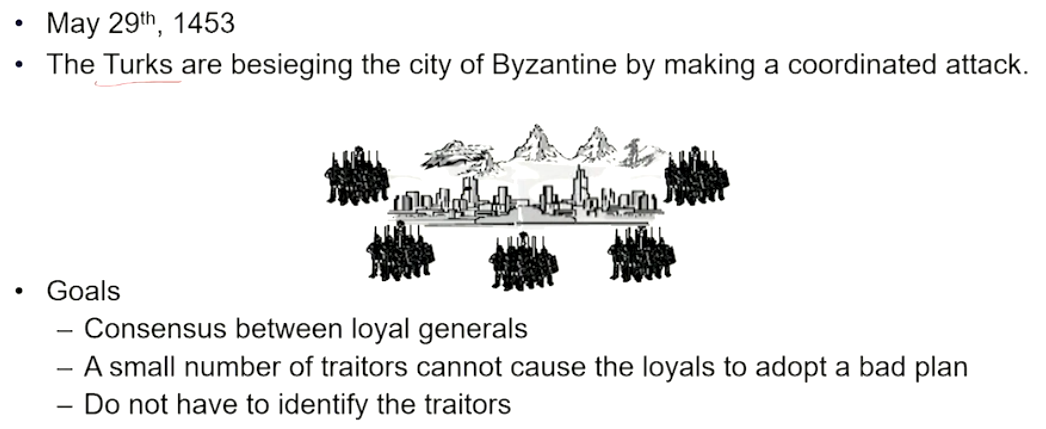

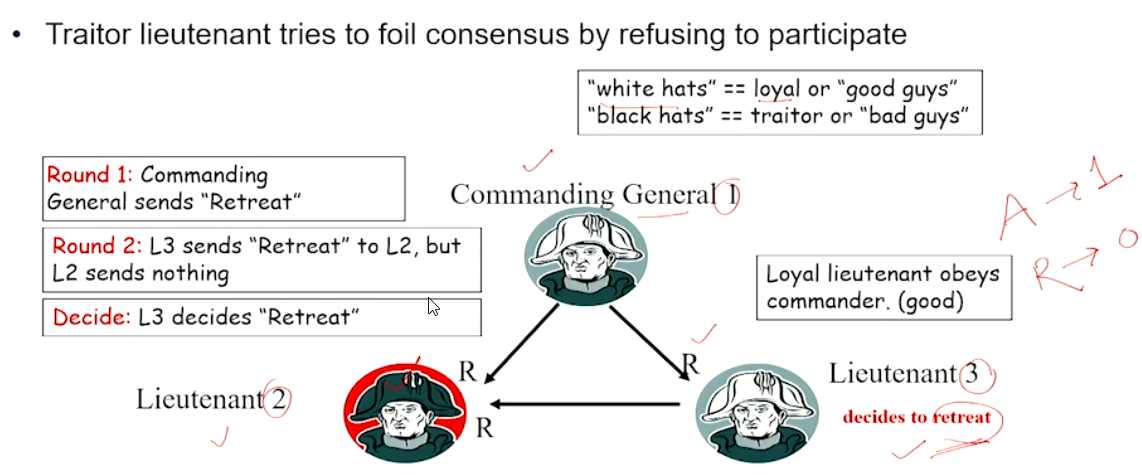

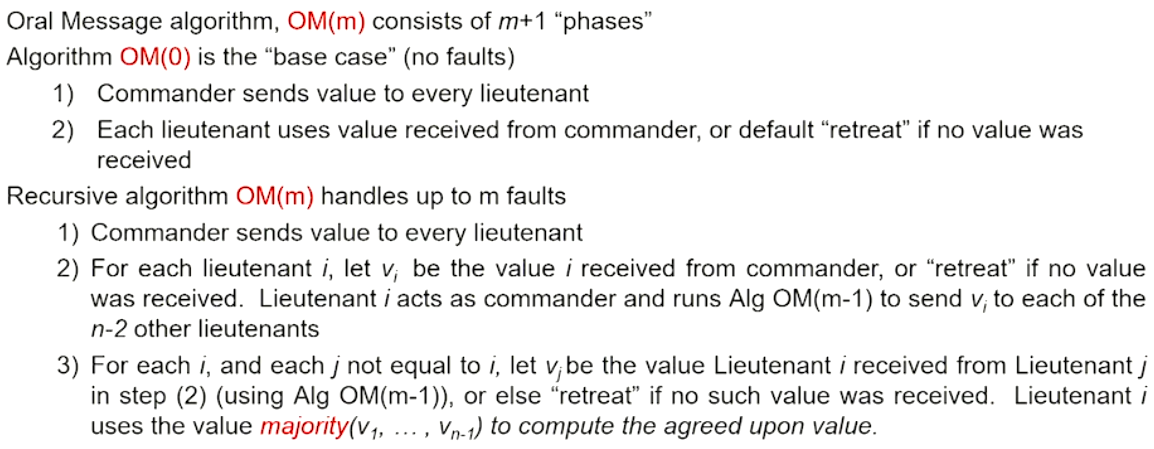

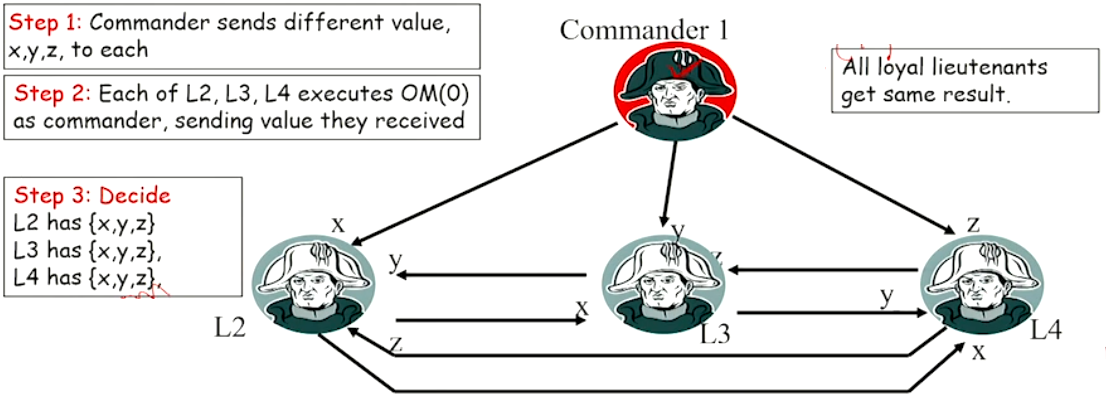

Oral Message Algorithm#

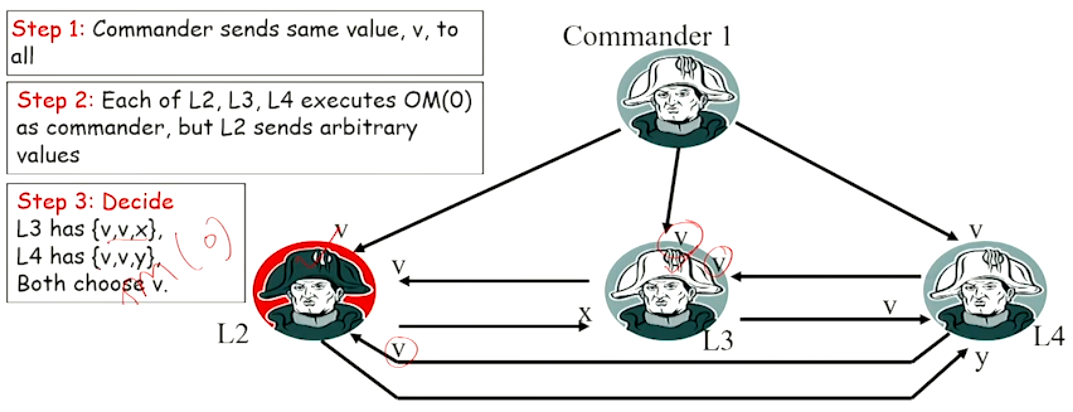

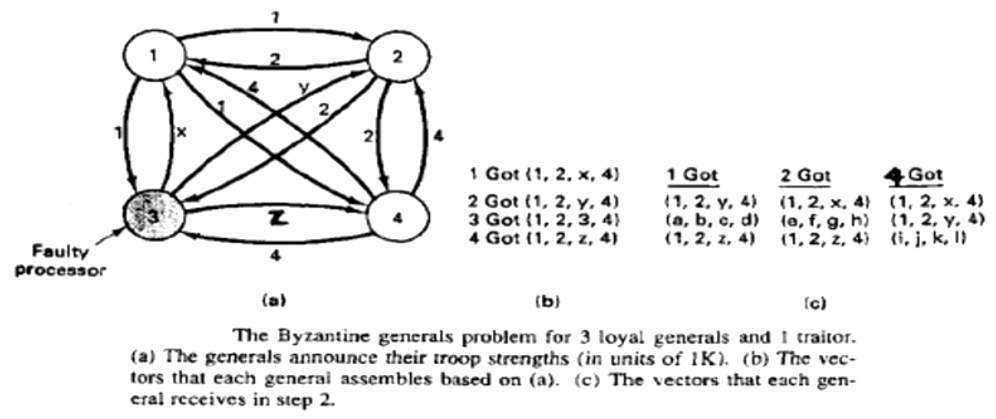

Example with \(m = 1\) and \(n = 4\)#

Another Example with \(m = 1\) and \(n = 4\)#

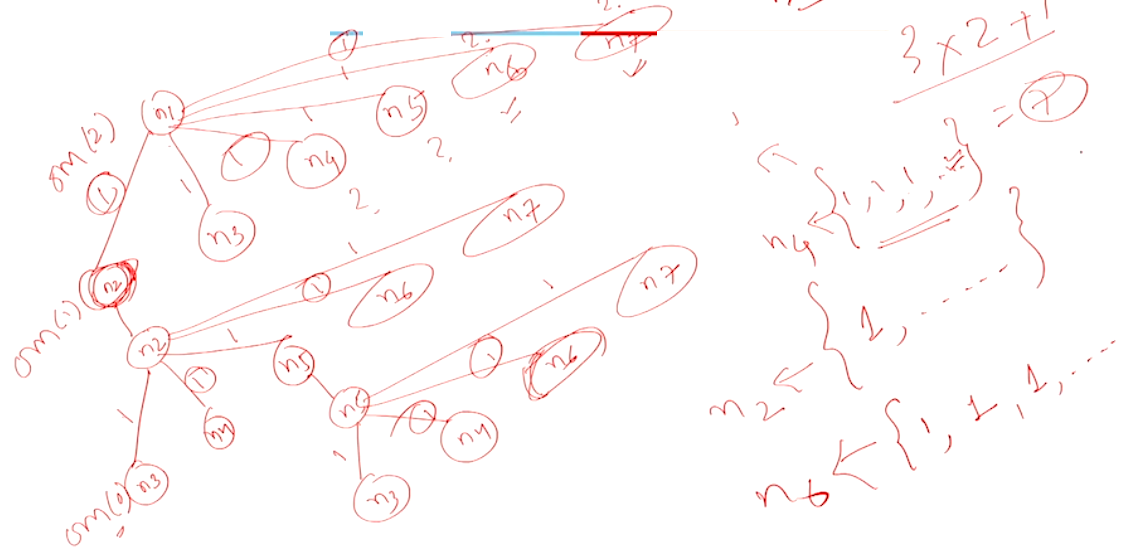

Example with \(m = 2\) and \(n = 7\)#

consider \(7\) nodes numbered \(n1\) to \(n7\) and assume \(n6\) and \(n7\) are faulty.

Round 1:

\(n1\) sends message to all the other nodes as part of the \(OM(2)\) operation.

Round 2:

\(n2\) to \(n7\) will run \(OM(1)\)

Round 3:

The other nodes that did not participate in \(OM(1)\) in the repective node will also send the values to other nodes

Once this tree is constructed, we need to find the max of the values in the respective vectors and decide what the values are in each node.

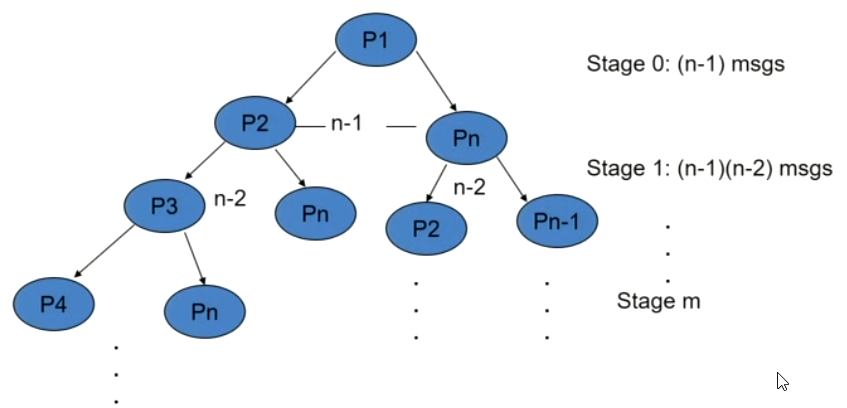

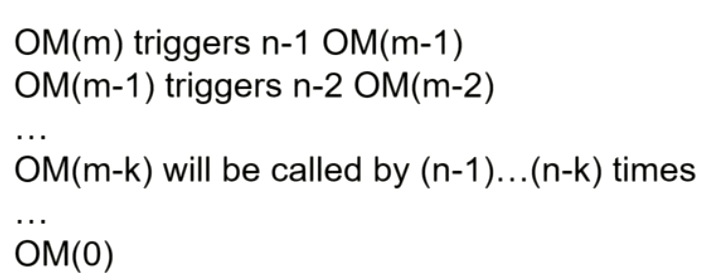

Complexity of OM#

Looking at the above graph we see that the number of messages required grows with every \(OM\) stage and the final number at the \(OM(0)\) would look something like:

This results in a complexity of \(\mathcal{O}(n^m)\)

Interactive Consistency Model#

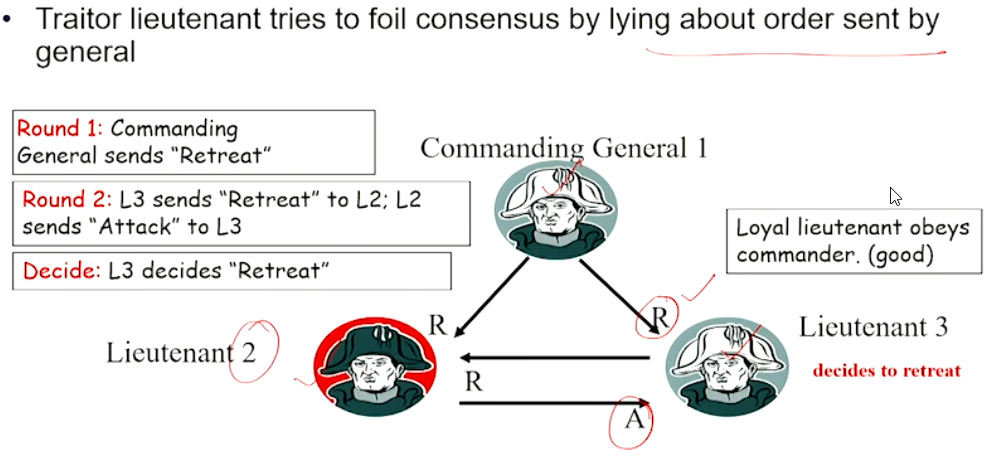

Signed message algorithm#